На сайте используются cookie файлы

The site uses cookie files

Данный сайт имеет возрастное ограничение!

This site has age restrictions!

Я подтверждаю, что мне, увы, уже давно исполнилось 18 лет

Phil Crozier, Europe Brand Ambassador – Wines of Argentina (WofA), @MrArgentina:

«My career in wine started in 1999, when Argentina was barely visible on the world wine map. I was tasked to make a wine list for a famous restaurant group in the United Kingdom, specializing in Argentine cuisine. Since my knowledge back then was rudimentary at best, it occurred to me that the wines should all come from Argentina. At that time there were 13 Argentinian wineries available in the market back then, with many now famous names yet to reach the UK shores. So much has changed in these short years. In a way, I have grown up with Argentina, and have been witness to one of the great wine and the fastest growing success stories of all time. This happened in just 25 years and Argentina continues to grow its influence».

What makes Argentina unique?

Wine is an essential part of culture in Argentina. So much so that it is the national drink, and also it is considered essential to life. Buenos Aires is the world’s second biggest consumer of wine, after Paris, in terms of cities. As we can see from the map of wine growing regions of Argentina, the main regions follow a line from North to South, along the Andes Mountains. In recent years, consumption of wine per capita has sharply decreased, like elsewhere in the world. The need to export has encouraged a drive towards high quality, so that they could compete on the world stage. But 75% of the wine made in Argentina is still consumed in Argentina, and that’s an important part of Argentina’s identity.

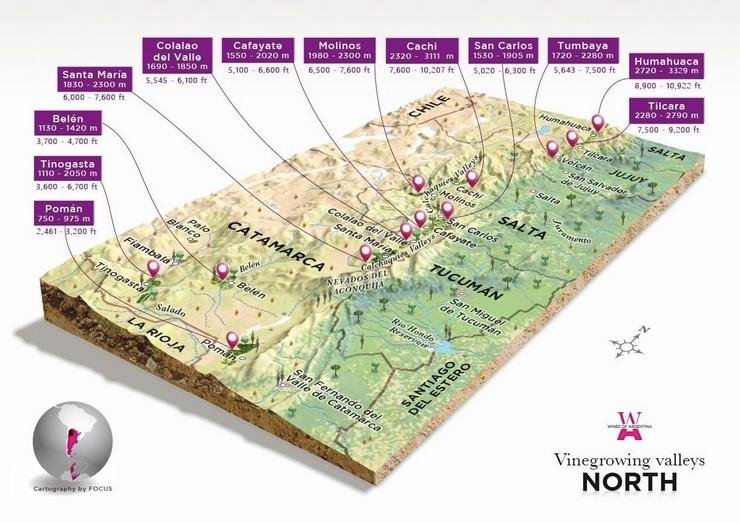

As we can see from the map of wine growing regions of Argentina, the main regions follow a line from North to South, along the Andes Mountains. It is these mountains that sustain the life of the vines. Without them, life would not be possible. Don’t forget, as we travel north, altitude becomes more important. The further south we travel, latitude becomes more of a cooling influence. The vineyard areas extend 3,800km from north to south, 23 degrees to 45 degrees south. Argentina is home to both the highest and most southern vineyards in the world.

For every 150m in elevation (west), we lose around 1 degree С in average temperature. As we travel north, we travel towards the tropic of Capricorn, and so we are getting warmer. Altitude provides the key to providing a cooling influence, so much so that the highest vineyards in the world are found in the provinces of Jujuy and Salta, with altitudes ranging from 1,600m to just over 3,300m. With increased altitude, lower temperatures, and less dense air, we increase UVb sunlight. For every 1000 m in elevation, UVb light increases by around 12,5%. This has a profound effect on the grapes. Water is also key. Rainfall is low along the Andes, ranging from 150 to 250 mm a year. We are in a desert. It is the Andes Mountains that provide the all-important snowmelt to feed the vines, with irrigation being the method. The Inca came as far south as Mendoza, and were supremely skilled in water management, a legacy which the Spanish inherited when vines were first planted by Jesuits, as far back as 1551. Today, the need to preserve water is key, with modern methods of drip irrigation taking its place alongside more traditional flooding techniques. Soils are mainly alluvial, but vary hugely, depending on where you are in the Andes. Fertility is very low, forcing the vine to search for nutrients through deep roots. As we move south, days grow longer during the ripening season, but sunlight is less intense. Temperatures decrease, but the desert conditions, like everywhere along the Andes, allow for big temperature shifts between night and day.

What does this mean for the vines?

Higher altitudes and lower latitudes mean cooler climates, whilst receiving up to 220 days of sunlight in a year. An increase in UVb increases the thickness and colour (tannin and anthocyanin) of the grapes, whilst cooler temperatures maintain acidity. When temperatures fall at night, the vine shuts down, maintaining the freshness. Sunlight, of course, kicks off photosynthesis the next day, and so on. Vines are shown to produce lower yields at higher altitudes, thus increasing natural concentration and flavour. Warmer temperatures will allow for softer tannins, so we get a stark contrast in wines from warmer areas in the east, to cooler temperatures in the west. In Mendoza, we can find the same range of temperatures in just 60 km, from east to west, as we do from Tuscany to Burgundy. This allows Argentina to possess a bewildering level of climatic diversity.

Is Argentina only Malbec?

Truth and myths Yes, Malbec is their calling card, and has been largely responsible for its success over a short few years, accounting for nearly 90% of all exported value. But there is so much more Argentina can surprise. Of the red varieties, Malbec accounts for 22,39%, with Bonarda Argentina, a grape originating from Savoie in France, second, in at 9,23%, followed by Cabernet Sauvignon at 7,2%, Syrah at 6.01%, Tempranillo at 2,81%, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc, Tannat, Petit Verdot and many more.

Malbec binds all of Argentina’s diversity, in that it is found in every winemaking province in Argentina. Argentina’s biggest advance in recent years has been in the quality of its white wines.

Torrontés Riojano (3,9%), a grape variety that is indigenous and part of a growing family of vines known as the Criollas, is a cross between Listán Prieto (known as Criolla Chica in Argentina) and Muscat de Alexandria, and spawned many variants. This grape variety thrives at high altitude in the North, whilst Chardonnay (2,99%), Sauvignon Blanc (0,99%), Chenin Blanc (0,92%), Viognier and Semillón succeed in the higher, cooler parts of the Andes.

Another Criolla variant of unknown origin, regarded amongst the Criolla varieties, is Pedro Pedro Giménez*, not related to the Spanish Pedro Ximénez variety, but widely grown for use in sparkling and table wines.

The pink varieties are mainly made up of the Criolla varieties, only found in Argentina, amongst them Criolla Grande, Cereza and Muscatel. These are mainly used for table wines. Whilst Malbec provides a platform for Argentina’s exports, it is regionality which will provide the future.

The Regions

In recent years, many regions and sub-regions have been granted GI (Geographical Indication) status. The first G.I. granted in the Americas was as recently as 1994, when the department of Luján de Cuyo in Mendoza was formed. So that we can understand a little more about the regions, let’s take a short trip from North to South.

The North

This includes the Provinces of Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán and Catamarca. Jujuy is a relatively new region, and is home to the world’s highest vineyard, with just 25H, but is growing. Salta is the dominant province, with the towns of Cafayate, Molinos and Cachi at its heart, nestling in the Calchaquí valley. This is defined by its altitude, dry and arid climate, and is the spiritual home of Torrontés, with 3,343.5H, accounting for just 1.69% of the planted surface in Argentina. But this region has seen plenty of new investment in the last few years, and is famous throughout the world for its unique style of wine. Tucumán, to the east, shares a very similar terroir to Salta, whilst Catamarca, to the south, forms the beginning of the Calchaquí valley. Some of Argentina’s oldest vineyards are found in these regions.

Cuyo

In the heart of the Andes, it is by far the largest wine area, making 95% of the wine in Argentina. La Rioja lies to the north, with 3,29% of the volume, and is largely made up of cooperatives, making wine for international markets on a big scale. Torrontés Riojano, Malbec, Bonarda and Syrah dominate the landscape. San Juan, to the south, is Argentina’s second largest province for wine, at 16,28% of the planted surface. The main valleys are Tulum, Zonda, Perdernal and Calingasta. In particular, the higher altitudes of Perdernal (1400-1500m) and Calingasta (1600m) are seeing big investment, and are names to watch out for in the future. Perdernal is unique in that it has flint at its core in terms of soils. Syrah, Malbec and some old Criolla varieties are San Juan’s calling card.

Mendoza is by far the largest province, producing 75,28% of all wine in Argentina, and is Argentina’s spiritual wine region. With 149,226.9H, altitudes range from 450m in the east (by far Mendoza’s biggest region) to 2000m in Uspallata, a new region to the north. Luján de Cuyo and Maipu form the ‘Primera Zona’, the heart of quality viticulture, and home to many of Argentina’s famous Bodegas.

The Uco valley, an hour’s drive from Luján de Cuyo, is Mendoza’s answer to cool climate. Divided into 3 departments, Tupungato, Tunuyán and San Carlos are divided by 2 rivers, Las Tunas and Tunuyán. Defined by high altitude and a close proximity to the front of the Andes (Cordillera Frontal), altitudes range from 1100m to 1700m. This is where the new cool school hangs out, and is largely responsible for inspiring many of Argentina’s young winemakers, who are producing wines with elegance and purity. This region has seen huge investment in recent years, with many of the older, more established Bodegas moving some vine production here too, in search of greater diversity. Most of the white wine revolution in Argentina is found here as well, with a big revival of old vine Semillón, Chenin blanc, as well as world class Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

Look out for G.I. names like Tupungato, Paraje Altamira, Los Chacayés, Vista Flores, La Pampa El Cepillo, La Consulta, La Carrera and Los Arboles. Although Gualtallary has yet to receive G.I. status, it is producing some of Argentina’s exciting new Grand Cru wines. Further South, and lying somewhat under the radar, is San Rafael, a two hour drive from the Uco Valley. It is dominated by a handful of large wineries, lies further east from the Andes, and is famed for its Cabernet Sauvignon.

Patagonia and the Atlantic

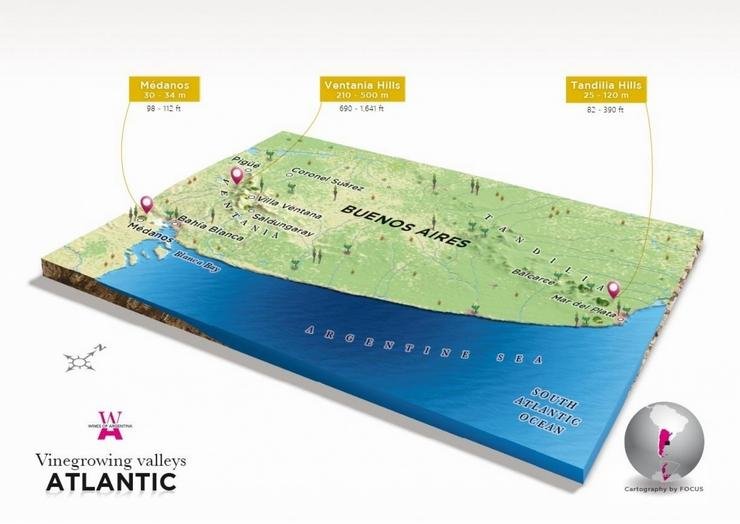

Out on the vast, open plains of windswept Patagonia are 4 wine Provinces, La Pampa, Neuqúen, Río Negro and Chubut. Here, latitude is the cooling influence, and forms the southern part of the Andes. Neuquén was planted at the turn of the millennium, whilst Río Negro is home to many old vineyards, between them accounting for just 1,83% of the vineyard surface of Argentina. Small, boutique wineries and new projects dominate the scene. Further south, in Chubut, cool climate varieties like Chardonnay, Semillón, Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir dominate. You will find wines with finer texture and elegance in these regions. Many old vines in Río Negro are being revived by younger winemakers. Buenos Aires and the Atlantic coast is home to 0,7% of Argentina’s vines, at just 149H, but it is a significant departure from the norms of Argentina’s continental climate. Again, cool climate varieties dominate, marking the beginning of maritime vineyards to add to Argentina’s rich diversity.

The Future

For some, Argentina’s future lies in a healthy respect for its past. Many forgotten regions are being explored again through ancient varieties, the Criolla’s being a case in point, particularly in the North and in eastern Mendoza. Criolla Grande, Criolla Chica, Cereza and Pedro Giminez will feature on wine shelves in the near future, with young wine drinkers looking for new stories and authenticity. For others, finesse will feature in wines that are less extracted, with less reliance on oak and a focus on purity. But for all, the focus for the future will be on regionality, with everyone finding their plot to rule. This will also secure the future of Malbec, with regional differences being key to show the huge diversity that Argentina has to offer. Expect to see more Cabernet Franc from the Uco Valley, Tannat and Torrontés from the north, Criolla Chica, orange wines, organic wines, wines made under Flor, use of native yeasts, and a near universal drive towards sustainability. I have never been more optimistic about the future of Argentine wine.

Glossary

Pedro Giménez is a white Argentinean grape with rapidly declining areas. Despite the similar name, the Spanish grape Pedro Ximénez has many differences, and ampelographers are not sure if the two varieties are related at all.

09.09.2024

08.06.2022

07.06.2022