На сайте используются cookie файлы

The site uses cookie files

Данный сайт имеет возрастное ограничение!

This site has age restrictions!

Я подтверждаю, что мне, увы, уже давно исполнилось 18 лет

It’s difficult to describe the moment when a wine region begins to rethink itself, but in Ribera del Duero the signs are impossible to miss. You feel it in the way growers speak about their vineyards – less about yields, more about strategy. You sense it in the quiet confidence of younger winemakers, many of whom have worked harvests in Burgundy, Barossa, Stellenbosch or Oregon and returned home with a different instinct for balance. And you see it clearly in the glass: wines that don’t rush to display their power, wines that breathe, wines that feel like they’ve stopped performing an idea of Ribera and started expressing one.

The region has been famous for its intensity for decades. Generous fruit. Altitude-driven concentration. A kind of monumental structure that defined its benchmark reds. But the most interesting part of Ribera today is not what it used to be – it’s how fast it is moving away from predictability. The vocabulary has widened. The texture has shifted. Power has not disappeared, but it has learned discipline.

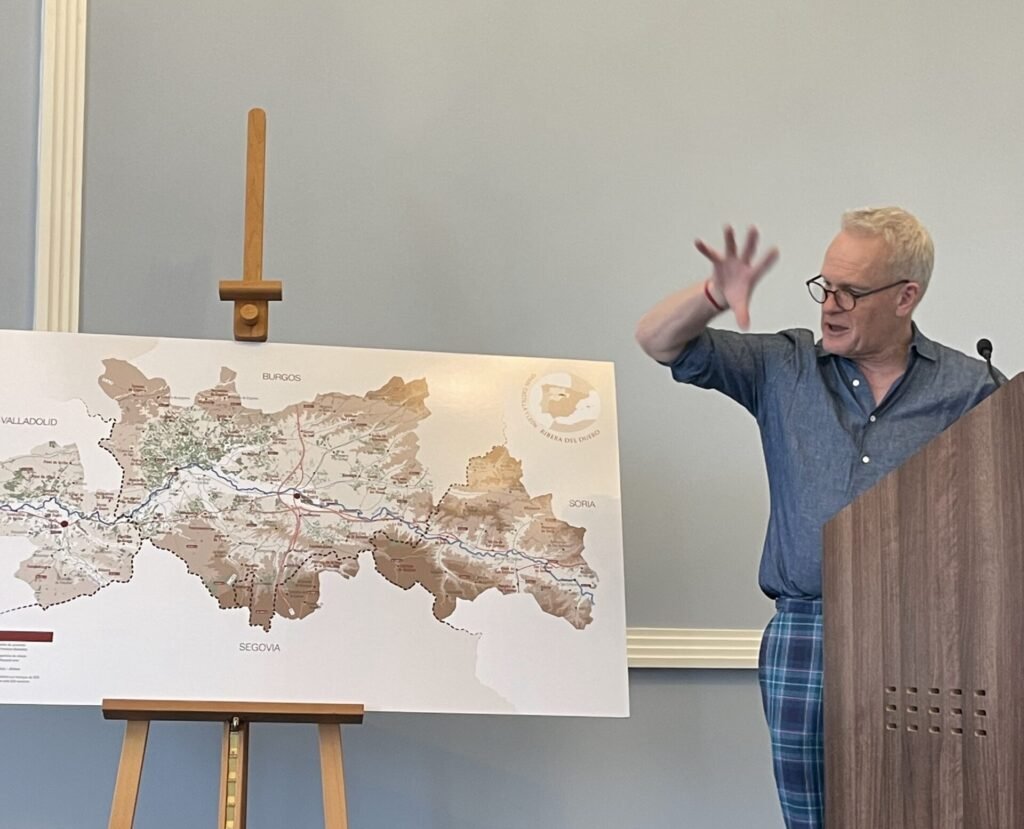

This evolution set the tone for my conversation with Tim Atkin MW in London. Atkin doesn’t speak about Ribera like an outsider assessing a distant landscape. He talks like someone who has walked the villages often enough to understand the region’s pulse. There was no drama in his voice – only clarity. “The region is moving faster than people realise,” he said, almost as if reporting a change in the weather. “Momentum is real here.”

I asked what exactly he meant. His answer came without hesitation.

Q: What stands out the most when you look at Ribera today?

Tim Atkin MW: “The acceleration. And the new generation. They’re doing things differently – but intelligently. Earlier picking. Bigger oak. Amphora. Not to copy anywhere else, but to articulate the plateau.”

This articulation – of altitude, of tension, of restraint – is the most exciting shift happening in Ribera. Wines are becoming more vertical. More deliberate. More concerned with proportion than size. It’s a stylistic evolution driven less by fashion than by necessity: climate change has shortened picking windows, exaggerated heat spikes, and made balance a strategic choice.

The New Generation

The younger winemakers shaping today’s Ribera don’t consider themselves rebels. They consider themselves caretakers of nuance. Their wines prove that generosity doesn’t have to be heavy, and that Tempranillo’s depth becomes more interesting when it’s allowed to stay fresh. They work with concrete and fountains, not because it’s trendy, but because it lets the altitude speak for itself. They talk about phenolics more than colour. About energy more than richness.

Q: How critical is this new generation for Ribera’s future?

Atkin: “Crucial. They’re the first to ask the right question: not ‘what was Ribera?’ but ‘what can Ribera be?”

The answer is already visible in the bottle.

Ribera’s reinvention isn’t limited to reds. Clarete – the co-fermented, gastronomic, defiantly local category – has reappeared with surprising authority. It is not a revival for nostalgia’s sake. It is the first stylistic movement the region has produced that belongs entirely to its own history.

And then there are the whites. Albillo Mayor, once considered peripheral, is now producing some of Ribera’s most distinctive wines. They are textural, elegant, structured – serious wines, not curiosities.

Q: Do whites now play a fundamental role in Ribera’s identity?

Atkin: “Yes. The best ones aren’t experimental anymore. They’re part of the region’s future.”

One part of the conversation that stayed with me was Tim’s breakdown of recent vintages, not because of the usual debate about “good” and “bad” years, but because his summary captured the rhythm of a region living on a climatic knife-edge. Ribera has always swung between Atlantic freshness and Mediterranean heat, but the oscillations have become sharper, the patterns more compressed.

Q: If you had to describe the last decade in one line, what would it be?

Atkin: “Hot years getting hotter. Cold years are getting rarer. And frost hits when you don’t expect it.”

His vintage map made the trend unmistakable.

The hot/dry sequence – 2009, 2011, 2012, 2015, 2017, 2020, 2022 – now reads like the region’s new normal.

Cooler or unsettled years – 2007, 2008, 2013, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2021 – are increasingly exceptions.

And the frost years – 2001, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2017, 2023, 2024 – underline how fragile the plateau has become.

Since 2003, only one vintage has begun harvest in October.

The rest started earlier, some dramatically so.

“2015 was the tipping point,” Tim noted. “From then on, everything moved forward.”

2023, 2024 and the upcoming 2025 are, as he said, “a bit of everything” vintages – the kind that force winemakers to react quickly rather than rely on patterns that no longer exist.

What this means for Ribera isn’t panic; it’s precision.

Picking windows shrink. Decisions tighten. Altitude stops being a theory and becomes a survival strategy.

A Voice From Inside: Pablo Baquera

From the inside, the evolution appears both inevitable and intentional. Pablo Baquera, the commercial director of the Consejo Regulador, sees stylistic change not as disruption but as alignment.

Q: Does the DO Ribera del Duero see this stylistic shift?

Pablo Baquera: “We see more freshness, more balance, more terroir expression. Innovation is happening – but authenticity stays. They aren’t opposites.”

He’s candid about the challenges, too.

Q: Is Ribera ready for the next decade?

Pablo Baquera: “We’re already adapting. Every year, something happens – frost, heat, hail. But this region has experience with extremes. Growers know how to work through them.”

His realism grounds the conversation. Atkin’s analytical clarity and Baquera’s on-the-ground perspective meet in the same place: Ribera is evolving because it must – and because it can.

“What next?” for Ribera del Duero isn’t a bureaucratic question.

It is a reality check.

The region can’t continue expanding indefinitely – not after the 2025 harvest, which became Ribera’s second-largest crop ever. Grape prices softened immediately. Demand didn’t match supply. More vineyards do not equal more value. The following strategic step isn’t growth. It’s discipline.

A soil map is long overdue. Altitude alone cannot explain Ribera’s diversity. Until the region classifies its vineyards by what they are, not by how long the wine spends in oak, its strongest producers are constrained by a system that measures ageing instead of origin. Great regions don’t hide their soils behind bureaucracy; they define them.

Irrigation is becoming the dividing line. In 2024, the stakes became clear: water will determine yields, but also identity. Used carefully, irrigation can preserve balance in extreme years. Used indiscriminately, it flattens differences and accelerates sameness – the very opposite of what the region needs.

Organic farming, once a footnote, has gained critical mass – 65 certified bodegas and counting. This is not ideology. It is self-preservation. In a climate this volatile, soil health is not a trend; it’s a survival strategy.

Machine harvesting versus hand picking… this is not a question of romance. It is a question of segmentation. The region will eventually have to decide which wines can be machine-harvested and which must be handpicked if it wants to maintain its integrity at the top.

Even technical discussions – massal selections, clones like CL-179, CL-98, CL-261, mixed vineyards — speak to a deeper truth: climate change does not reward uniformity. Ribera’s genetic and viticultural diversity is not an aesthetic detail. It is a competitive advantage. It must be protected, not flattened.

And then there is the new generation – educated abroad, stylistically fluent, unafraid. Their wines already point toward a future where purity matters more than extraction, shape more than volume, and clarity more than intensity.

The next chapter will not be written by hectares or yields.

So where does that leave Ribera del Duero?

Not in crisis. Not in transition.

In definition.

The region is moving quickly – faster than its own reputation, faster than many outsiders realise. It is learning to treat power as material, not message. It is rediscovering its own diversity. It is reconsidering growth. It is rethinking identity through whites, claretes, old vineyards, and new philosophies. And it is embracing a generation that sees no conflict between respecting tradition and redefining it.

I asked Atkin one final question – the only one that matters when a region stands on the edge of its next decade.

Q: Where do you see Ribera in ten years?

Atkin: “If the region makes the right choices – at the top. Truly at the top. The potential is extraordinary.”

Potential is not a guarantee.

But Ribera del Duero feels like a region finally ready to earn it.

It is no longer shaped by what it once was.

It is shaped by what it refuses to remain.

And perhaps that is the most exciting thing:

Ribera is not standing still.

Not for a moment.

⇒ Join our social networks ⇒ Optimistic D+ editors will take this as a compliment.

⇒ Every like is taken as a toast!

20.02.2025

25.06.2024