Увага! На сайті використовуються cookie файли.

The site uses cookie files

Даний сайт має вікове обмеження.

This site has age restrictions!

Я підтверджую, що мені, на жаль, давно виповнилося 18 років

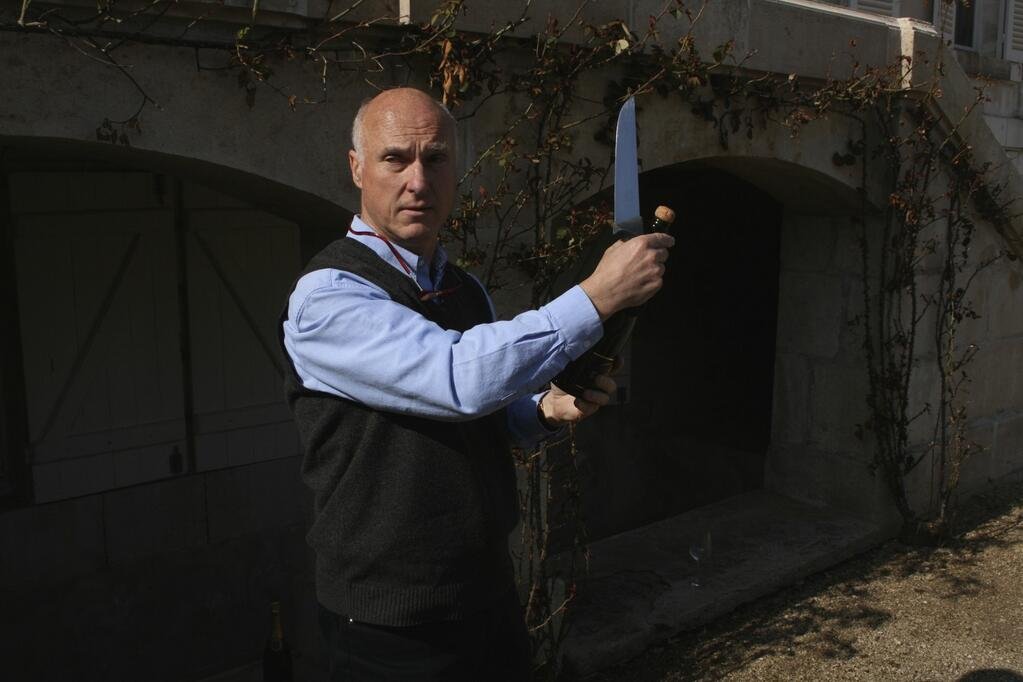

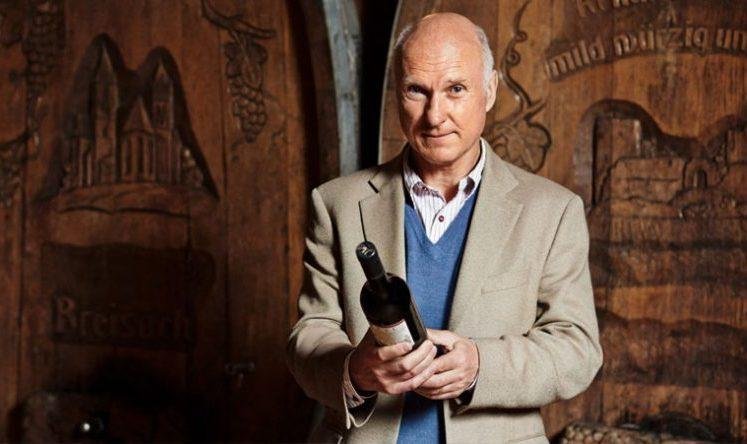

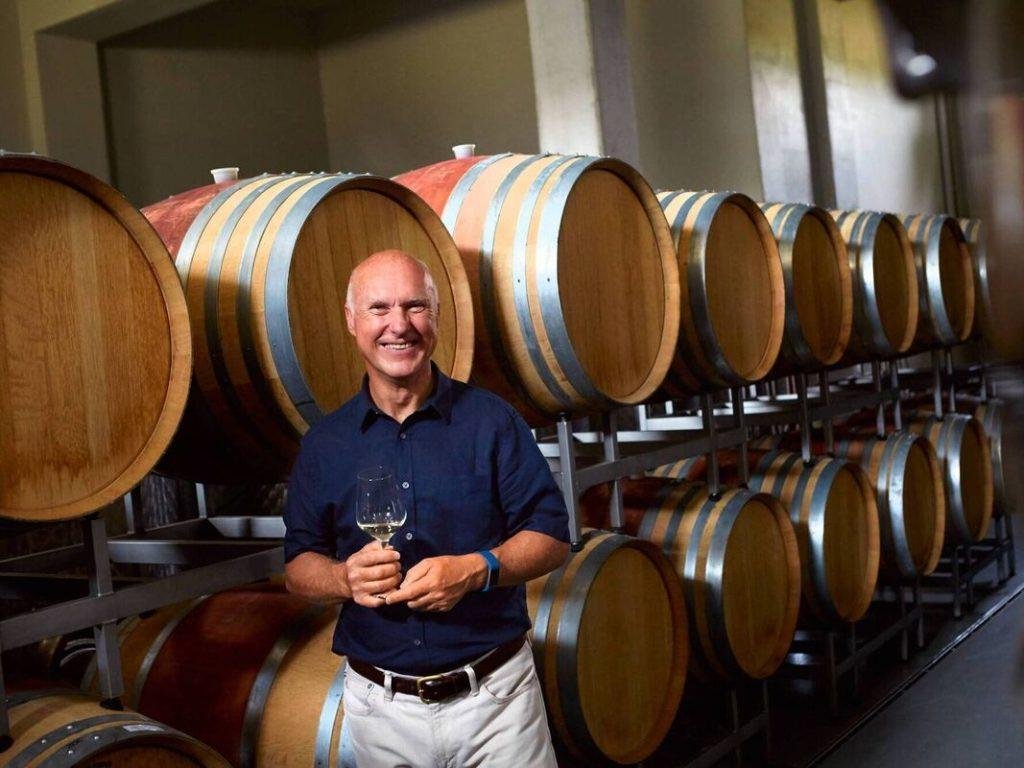

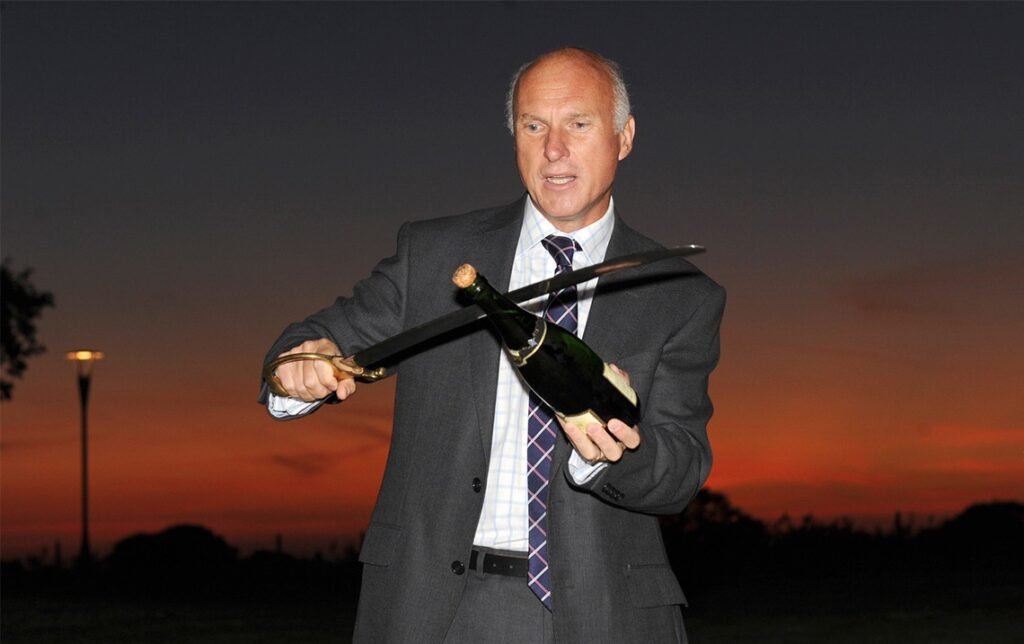

In this enlightening conversation, Richard Bampfield MW takes us on a journey through his expansive career in the wine industry, from his formative experiences in retail to becoming a Master of Wine and a leading authority in the sector. Richard reflects on his global perspective, honed through years of international travel and work, which significantly shaped his understanding of wine’s evolution and its sustainable future. With a focus on lifelong learning and a deep commitment to promoting sustainability in the wine industry, Richard Bampfield discusses the nuances of wine tasting, market dynamics, and the crucial role of tourism in shaping wine regions globally. His insights offer a rich exploration of the challenges and opportunities facing the wine industry today, making this discussion a must-read for anyone interested in the future of wine.

VB: Richard, could you describe your initial journey into the wine industry? Was it a career you pursued intentionally, or did the opportunities find you? Additionally, did family influence play any role in your decision to enter this field, or was it solely a personal decision?

RB: I essentially entered the wine world on my own. Growing up in Britain during the 60s and 70s, my family, like most, rarely drank wine unless we were on holiday in France, Italy, or Spain. It was during these family trips that I first developed an interest in wine – it seemed special, something we only enjoyed on vacations. My appreciation for wine grew during my university years in France, where I studied language and literature, influenced by student culture and the affordability of wine. My proficiency in French was quite strong upon graduation, though not perfect, and I wanted to improve it. This background in French, combined with a year spent in France, deepened my understanding of wine as I was surrounded by friends involved in the industry. After university, unsure of my next steps but wanting to use my French and continue my engagement with wine, I turned to family friends in the business for guidance. This led to my first job in wine shops and felt like a natural progression, combining my interests and studies, though no one in my family had a background in the industry.

VB: So, you started your career in retail, focusing on selling wine and interacting directly with customers. Is this what you mean when you talk about how you first got involved in the industry?

RB: Absolutely. I worked in wine shops for about eight or nine years and absolutely loved it. That experience is one of the reasons I really enjoy conducting tastings with the public now. I’ve always relished the opportunity to talk to people about wine, listen to their opinions, answer their questions, and understand their process of selecting a bottle of wine.

VB: Are we discussing how you entered the wine industry in the 1980s? And did you start your pursuit of the Master of Wine recognition during the 90s?

RB: I worked in the wine industry throughout the 1980s and completed my initial examinations, including WSET levels two to four, during the 1990s. Initially, the idea of becoming a Master of Wine seemed beyond my reach. However, in 1988, I took a year out to travel, as I was single and had the time to explore. During this period, I engaged primarily in wine-related work. I spent time in California, worked for a vineyard in Australia, and visited New Zealand and Argentina. At that time, traveling to these countries was quite exotic, as they were not major wine exporters until the 1990s. Working in vineyards and cellars abroad was invaluable, as it filled the knowledge gaps I couldn’t bridge back in England, where we lacked high-quality producers that time. Upon returning from my travels, I stumbled upon a Master of Wine exam guidebook. After reviewing it, I realized I had acquired the necessary knowledge and confidence to attempt the exam. I took the Master of Wine exam a few months later. And it was successful.

VB: Could you tell us about your experience with the WSET during your time there? How do the programs from back then compare to the current structure of WSET today?

RB: First of all, the basic structure of the WSET program remains similar to what it was originally, though it’s now better aligned with the UK’s National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs), integrating it with other subject-matter qualifications. This alignment has marked a significant improvement. The main difference today is the distinct separation between the levels, which aids this alignment. WSET Level 2 is a substantial step up from Level 1, Level 3 advances further from Level 2, and Level 4 is a major leap from Level 3. This progression makes Level 4 an excellent foundation for those looking to embark on the Master of Wine program. It’s a much bigger commitment and provides a closer stepping stone to the Master of Wine than when I was a student. Overall, the WSET has grown significantly since the mid-1980s when I first took their classes. It’s become much more professional, better resourced, and more internationally focused. For anyone entering the wine industry or looking to advance, I still believe the WSET offers excellent training. The growth in the number of people taking WSET courses certainly reflects the quality of the class.

VB: Was there a particular country or region that significantly inspired you and influenced your career in the wine industry over the years?

RB: That’s a good question. Chile was quite influential for me. At the time, Chile’s main market was South America. It’s interesting because the wines they considered top-tier in 1988 seemed old-fashioned to me. They weren’t well-suited for export markets initially, and they were just starting to realize that they needed a more fruit-driven style to succeed internationally – something they began to understand with their early exports to the United States. Argentina had a similar scenario; their perception of top wines differed significantly from what the export markets expected. Meanwhile, California was a different world altogether. By then, it was already producing world-class wines, and getting to know Napa Valley better was truly a privilege – I absolutely loved working there. I met other Europeans during that period; I’m still in touch with them today and have maintained friendships with people from France, Algeria, and the UK. Making these connections was one of the highlights of my time in California. I spent the longest period in California, which perhaps is why it made the biggest impression on me. My time in Australia was also formative; I spent two months working in vineyards, two months in a cellar, and two months traveling around the wine regions, totaling six months. Australia’s wine industry was quite sophisticated already, especially in terms of viticulture and winemaking, which I greatly admired. Upon returning, I took a job with the Australian company Brown Brothers about nine months later, largely due to the impressions from that trip. What stood out to me was their business acumen – their realistic yet ambitious approach to managing their business and exports. It was the first time I felt like I was working with real businessmen. Although I do not consider myself a natural businessman, I found it incredibly fulfilling to work with people who understand how to effectively manage operations, and I thrive in that environment. This was another significant lesson I took away from my time in Australia.

VB: Could you share how stepping into the role of Operations Director at Brown Bros influenced your career trajectory?

RB: Yes, I held a position with Brown Brothers. When I joined their UK office, which managed all European wine exports, I quickly became the general manager within a couple of years, a role I enjoyed for about seven years. I was in charge of managing Brown Brothers’ exports to Europe during a period when Australian wine exports were booming. Part of my job involved managing allocations, which was relatively straightforward given the high demand for our wines, not just in the UK but across Europe as well. This demand made it easier to sell the wines and also allowed me to travel extensively across Europe, gaining a deep understanding of the various market structures. I learned the nuances of selling to retail versus trade and developed strategies to effectively navigate the Scandinavian market. So, it was a really good time – actually, it was a fantastic time – a great opportunity to learn about all these things and to help the Australian wine business move forward.

VB: You’ve mentioned that commercial acumen isn’t your strongest suit as a general manager. Could you elaborate on that perspective?

RB: I am really interested in the wine business and follow it quite closely. I enjoy understanding different business models, approaches to the market, and types of marketing strategies. So, while I have a keen interest in business, I’ve discovered that I’m not a natural general manager. I actually enjoy the wine aspect more than the spreadsheets. I believe that to be a good general manager, you need to enjoy the spreadsheets and the budgeting side of the business.

VB: Could you share details about any mentors or influential figures who significantly impacted your career? Are there specific individuals, whether through personal acquaintance or inspiration, who played a crucial role in your development?

RB: When I was working in retail, I was fortunate to work with two excellent retail managers. Both were much older than me and nearing retirement. What fascinated me was their common trait: they didn’t know much about wine, but it didn’t matter, because they were exceptional with people. They had a natural curiosity about each customer, making efforts to get to know them and quickly becoming friends. Most customers realized these managers weren’t wine experts, but they trusted their judgment because the managers took the time to understand their preferences and needs. This experience taught me the value of a salesperson understanding whom they are selling to. A good salesman can make customers enjoy a bottle of wine even if it’s not exactly to their taste, simply because they’ve enjoyed the purchasing experience. However, these managers often frustrated other staff by spending too much time with one customer while neglecting others. It’s a fine balance, but the essential lesson was clear and invaluable – they taught me a lot about people and how to sell, or about an approach to selling anywhere and to anyone.

Additionally, I worked at Brown Brothers in sales, where I admired the business rigor, though I realized the business side was not for me. I respected how their professionalism contributed to financial success. In the UK, we sometimes undervalue commercial success, almost as if making money is slightly shameful. I admire the American approach, which is more openly money-oriented. I think there’s a middle ground between the two, and Australia strikes a good balance. What I appreciate about Australia is that it has managed to find that middle ground effectively: they aim to take good care of people – I do believe they look after employees well in Australia and they’re respectful. However, they also understand that their business must be financially viable because they have a reputation to uphold.

VB: Lidl is known for its low prices, which has sparked some controversy. As one of your main clients, could you explain how Lidl’s pricing model impacts the producers who supply their products, particularly in the wine industry? How do these relationships affect the broader market and the perception of quality within the industry?

RB: Lidl often faces criticism for its low prices. There’s a common misconception that low shelf prices mean producers, like farmers, are paid unfairly low wages, suggesting that Lidl pressures them on price. This is simply not true. Producers who supply Lidl, or any supermarket for that matter, benefit from the volume of sales these retailers provide. The volume is critical as it forms the foundation of their business: knowing they have a steady revenue stream from Lidl allows them to plan and stabilize their production. It’s not just about price; these contracts provide security in volume, which is crucial for producers. This foundation allows them to explore other revenue streams by diversifying their product mix. Often, it’s the cooperatives supplying these supermarkets, and I believe cooperatives are the unsung heroes of the wine industry. While the spotlight often falls on small artisanal growers who capture critics’ acclaim, many small growers are happy to simply cultivate their grapes and sell to cooperatives, supporting their livelihood and that of their families. It’s these cooperatives, supported by supermarket purchases, that sustain these small growers. Supermarkets demand high standards for the wines they purchase, and cooperatives excel in meeting these requirements. So, my shout out is to the cooperatives across Europe, doing an excellent job amidst misconceptions about quality and conditions. They are the real backbone of the industry, keeping small growers afloat and ensuring quality production.

VB: Could you elaborate on how you perceive the general wine trends across Europe and the rest of the world? This particularly concerns the consumption issues among the new generation, which tends not to drink wine, and some local challenges where many experts currently see little hope for significant growth. Considering the era we are living in, what do you think might happen in the future?

RB: What concerns me is witnessing the wine world in a fragile position. I don’t see a strong future for wine as it currently stands. The struggle many in the industry face is disheartening, and although I wish for greater success and profitability, it seems a distant reality for many producers. Regarding global trends, wine consumption is declining worldwide, a trend that’s been noticeable for the past few years. This is particularly concerning in the United States, which has been a major market for many wine producers. The fluctuating market in China and ongoing trade wars add to the uncertainty, impacting the potential for export success. Concerns about younger generations not drinking wine don’t worry me as much. Historically, wine has been perceived as more of an adult beverage, something people might grow into. I’m not suggesting we should ignore it, though it worries me less than it does others. I think there are other, more worrying things – climate change, for example, concerns me a lot. Climate change poses a real threat, not just because of rising temperatures, which vineyards can potentially adapt to by modifying practices and grape varieties, but because of the extreme weather conditions it brings – severe droughts, heavy rainfall, and frost. These extremes, which are difficult to predict and prepare for, directly affect crop yields and business stability.

Another significant challenge is the stance of the World Health Organization, which claims that no level of alcohol consumption is safe. Such statements, backed by what many consider incomplete data, could influence governments to impose higher taxes on alcohol, including wine. This is problematic, especially considering the substantial social and economic impact wine has in countries like France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. The wine industry is indeed fragmented, which economically, is a disadvantage. Consolidation might be necessary for survival, allowing producers to achieve economies of scale and build stronger brands. Unlike beer and spirits, which are heavily brand-driven, the wine industry lacks strong brands, making it harder for consumers to make purchasing decisions. We need more recognizable wine brands, which I believe will come through greater consolidation and a better balance of supply and demand. In many parts of the world, producing wine isn’t profitable, especially at the lower end of the market. Some vineyards are growing grapes that no one wants, and it might be more sensible to repurpose this land. As long as we produce an excess of wine, the price pressure will continue to drive the industry into a less profitable state. I don’t foresee a near future where the demand for wine increases significantly enough to change this trajectory.

VB: How do you view your involvement with the Sustainable Wine Roundtable (SWR): as a natural progression of your career, or is there a deeper commitment to the cause that motivates you?

RB: It all started with a conversation about five years ago with Toby (editor’s note: Tobias Webb is the co-founder of Sustainable Wine Ltd, alongside Agatha Pereira) during an interview on sustainability. We discussed the plethora of sustainability certifications worldwide and how they essentially dilute each other due to lack of public recognition. I think one of us mentioned needing to do something about it. We hoped we could, and though I didn’t think much of it initially, Toby began to take action a month or two later. He’s a very dynamic individual, and once he commits to something, he gives it his all.

Since then, the initiative has grown. We believe we can make a difference, which has turned our idea into something tangible. The ultimate goal remains similar to what we initially envisioned – an organization that, over time, would simplify for consumers the identification of sustainable wine products. But now, there are additional objectives. Do I see this as a natural progression of my career? Not necessarily, although I’ve always wanted to leave a legacy beyond just earning a living. I’ve had discussions with friends and family about wanting my life to contribute to something meaningful. So, when this opportunity with Toby came up, it felt like the right moment to dedicate my time. What will we ultimately achieve? I’m not sure; we don’t yet see the finish line, but we’ve already made some significant impacts.

VB: Could you explain in a few words what SWR is about for our readers?

RB: The Sustainable Wine Roundtable has significantly evolved from its early days into a substantial organization. We are a member-based group where membership fees are scaled based on the company’s wine turnover.

Unlike typical sustainability certifications that focus solely on producers, we encompass the entire wine value chain, including producers, glass manufacturers, cork producers, logistics companies, other standards organizations, retailers, distributors, and importers. This comprehensive approach allows us to address sustainability holistically across the entire spectrum of the wine industry. Our goal is to unite all these stakeholders to build a sustainable future for wine by fostering communication and collaboration to avoid duplication and cover all bases.

We currently have over 120 members worldwide, ranging from very large to small entities. It’s crucial that we represent and listen to both the smaller players and the larger ones.

One of our projects is creating a protocol for managing vineyards sustainably, addressing the proliferation of certification standards by developing a framework to assess and benchmark them. This helps distinguish what each standard does well and where there is room for improvement. We recognize that the demands and costs of sustainability vary across regions, but we aim to establish universal standards that encourage continuous improvement in sustainability.

This task is delicate; some see new standards as a threat, but we must be pragmatic and focus on the collective goals of profitability and environmental improvement. We maintain close contact with other organizations engaged in similar work, such as those involved with the Porto Protocol, which is a fundamental framework for us.

International wine organizations, including the OIV, perform excellent work in related fields, and it is vital to ensure that we are supportive of each other’s efforts without being overly inventive with their terms.

Collaboration is essential – not just within SWR but also with these external bodies – to ensure we support each other’s efforts and avoid reinventing the wheel. It’s about learning from one another and building a stronger business through cooperation. There is still much work to be done, but we are committed to making significant strides in sustainable wine production. We believe in working together to achieve a more sustainable and profitable future for the wine industry.

VB: How have your roles as a presenter, writer, and judge influenced the narratives in wine education? What goals are you pursuing, and what narrative are you promoting in the wine world?

RB: I write very little; there are many who can do that better than I. My strength lies in speaking about wine, which I love. I participate in a lot of consumer events and engage actively on social media. I believe I articulate my thoughts on wine well, in a way that resonates with people. I’m not overly technical; I emphasize the drinkability and joy of wine. For me, the pleasure of drinking wine should always be paramount.

I enjoy discussing wine with both consumer and trade audiences, keeping up with global wine trends and business aspects. I think that as Masters of Wine, we almost have a duty to stay well-informed, so that we remain accredited to the title. If invited to speak at webinars or conferences on topics I’m knowledgeable about, I’m always eager to participate as I really enjoy it. I also like a lot moderating discussions, as it allows me to delve into various subjects and continuously expand my knowledge.

Regarding wine judging, I do it for two reasons: one – because when you take the Master of Wine exam, you are trained in the blind system, and the best wine testers in the world are the Master of Wine senior students. It’s now the absolute peak of their hours; they are doing blind tastings probably every day and practicing. They may not be perfect, but it makes you the best you can be. So the best I ever was as a tester was when I was a Master of Wine student. And effectively, I’d say I was going down from there as a blind tester – I’m just being realistic. Being in competitions, being a wine judge enables you to continue to calibrate your palate to ensure that you’re still tasting consistently with other people, and that’s really important for a job like mine, where I’m assessing wines when I’m giving you my wine scores. But sometimes, when I’m writing a tasting review, I need to ensure that my palate is still consistent with my peers.

Secondly, judging offers a mentoring opportunity. Often, younger professionals and those new to the trade are on the panels, and they value insights from experienced individuals like myself. I believe this mentorship aspect is vital for those entering the industry, and I enjoy it.

VB: Richard, you’ve recently joined as a judge for this edition of the Wine Travel Awards. Could you share any thoughts or insights about your new role?

RB: I truly applaud what you’re doing! Tourism is crucial, especially given the fragile economic future of wine. Wine regions are often naturally beautiful – typically located in mountainous areas less suited for other crops – making them attractive destinations. We’re already witnessing the impact of tourism in places like South Africa, California, and Australia, where it’s becoming a significant part of the wine landscape. Economically, this is hugely beneficial for the industry.

Through the Wine Travel Awards, I see immense value for producers. They can learn from global best practices and gain insights on how to enhance visitor experiences. I’ve often encouraged French producers to visit regions like Stellenbosch or Californian valleys to observe and adopt innovative tourism practices. While not perfect, the exchange of experiences is invaluable, and many European producers could learn from such exposure.

For consumers, it’s equally beneficial as wine tourism fosters community among those who share a passion for wine. It’s about sharing joy and experiences with others, both familiar faces and new acquaintances. The Wine Travel Awards could serve a similar role to the Michelin Guide for food enthusiasts who use it to plan visits to places like New York or San Francisco. It could guide wine lovers visiting new regions, enhancing their travel plans and overall experience. This connection benefits both the public and producers, making wine travel not just enjoyable but also more accessible and informative.

VB: I’d like to highlight your ongoing support for Ukrainian wine producers through various events and initiatives. You’ve been actively involved in supporting Ukraine’s wine industry. What motivates you to be part of this initiative? Can you share any standout examples of Ukrainian wines or projects that have left a lasting impression on you?

RB: When the war broke out in Ukraine, it was clear that many Ukrainians needed to find safe places to live abroad. Unexpectedly, we ended up hosting a Ukrainian mother and daughter for several months. It was a delightful experience for us, even though the mother spoke little when they first arrived. They have since returned to Ukraine, and while it was our pleasure to help during their time of need, we cherished the time spent together.

Around the same period, I was involved with a stand at the London Wine Fair featuring Ukrainian producers. There, I met Vitaly, the CEO of Alcoline, which produces wines under the Bolgrad trade name, and I was impressed enough by the wines to see potential for them in the UK market. Vitaly, who has visited the UK several times, articulated passionately about the necessity of keeping Ukraine’s economy running to support their country during these times. He emphasized the importance of exporting Ukrainian wines, especially now that Ukraine has gained global recognition – albeit under tragic circumstances. I’ve been actively helping him and staying in touch, working to support the export of Ukrainian wines, which is on the rise.

Additionally, I’ve recently connected with representatives from Shabo on a few occasions. We participated in a wine tasting in Warsaw, where numerous Ukrainian wines were sampled to identify those suitable for export markets, including wines from Shabo. During the event, I had an engaging conversation with a representative from Shabo. I particularly enjoyed the wines from Shabo; they, among others, represent some very good Ukrainian producers.

In all these interactions, I leverage my network within the wine industry to assist wherever I can, using my expertise in distribution and market knowledge. This is simply applying what I know to help in a logical way, but I’m genuinely impressed by everyone I’ve met and the quality of the wines.

⇒ Join our social networks ⇒ Optimistic D+ editors will take this as a compliment.

⇒ Every like is taken as a toast!

Photo: lidl.dk, lidl.co.uk, oxfordwineclub.org.uk, sustainablewine.co.uk, bleedingheart.co.uk

08.02.2026

27.11.2025